One of the most legendary and storied neighborhoods of Birmingham is Woodlawn. It is a community, anchored by one of the great public high schools of Birmingham, that has produced many citizens who contributed to the life of our city and has had an impact beyond the neighborhood itself. In a short post like this true justice cannot be done to the rich heritage and legacy of Woodlawn. However, we hope that this narrative brings together many of the diverse threads that make up the fabric of the community’s historic arc in a concise piece.

The origins of what we now know and love as Woodlawn trace back to 1815 when the Hawkins, Riley, Eubank, and John Smith families became pioneering inhabitants of what they called Rockville. According to the National Register of Historic Places, the neighborhood was documented as one of the earliest settlements in Jefferson County. A pivotal shift happened in 1838 when pioneer Obadiah Wood acquired 400 acres on Georgia Road for the sum of $1,500. The three generations of Wood family members that came with Obadiah would have a lasting impact on the area. However, it wouldn’t be until 1886 that the community was ultimately renamed Woodlawn after the Wood family.

When the Wood family migrated from South Carolina to the Woodlawn area, the town was known as Rockville and only had a small post office. As the years and prosperous endeavors unfolded, Obediah Washington Wood Sr., son of Obediah, emerged as a prominent figure and built up the community significantly. He not only established the area’s first general store, official post office, and sawmill but also facilitated the necessary pathways for railroad and streetcar infrastructure. As part of his enduring legacy, he contributed land for the construction of four churches, a school, and facilitated the settlement of former slaves in the neighboring Zion City. The first railway came through the valley in 1870, at which point the settlement was renamed Wood Station and began to grow steadily.

But the growth and success of the community wasn’t the result of only one family. Many other settlers began to make their way to Jefferson County. Additionally, generations of slaves who labored on the land of Jones Valley contributed to the growth of the community. Thannie Wood was born a Wood slave and had 13 children. Although no records of her ancestry are available, she was one of many enslaved families that lived and labored in and around Woodlawn.

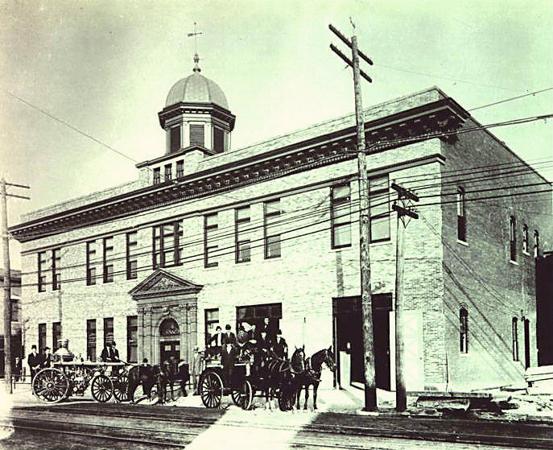

In 1871 the City of Birmingham was established to the west of the existing community. In 1888, John T. Hood established the Woodlawn Land and Improvement Company with an initial $50,000 capital which greatly influenced Woodlawn’s growth as both a commercial center and residential suburb. Streetcar lines connected many of the suburbs to the core growing city of Birmingham, increasing growth outside of Birmingham’s City limits. The Woodlawn Depot was built in 1904. The population of Woodlawn surged to 1,506 by 1890, a remarkable 1592.13% increase in a decade. The “Greater Birmingham” campaign in 1898, sought to expand the city through suburban annexation to bolster the census, tax base, and city services.

Annexed into the City of Birmingham in 1910, Woodlawn featured locally renowned commercial, educational, religious, and civic institutions and facilities throughout the early and mid-twentieth century. After annexation, Woodlawn entered its most prosperous phase and adopted a lasting physical character. Despite lacking major industries or planned company housing, Woodlawn found success due to its proximity to downtown and its strategic location along streetcar lines that connected Birmingham to neighboring suburbs such as East Lake and Gate City. The height of development was reflected, in part, by the phase of second-generation buildings by most of the community’s religious institutions.

By the 20th century, challenges from automobiles, economic depression, and world war arose. However, the use of street rail service persisted because of wartime gasoline rationing. In 1931, the bus service was introduced to Woodlawn, yet it took over two decades to replace the streetcar. The Tidewater streetcar line, which operated along Third Avenue South, running from Ensley to East Lake since 1913, saw its last ride on April 19, 1953.

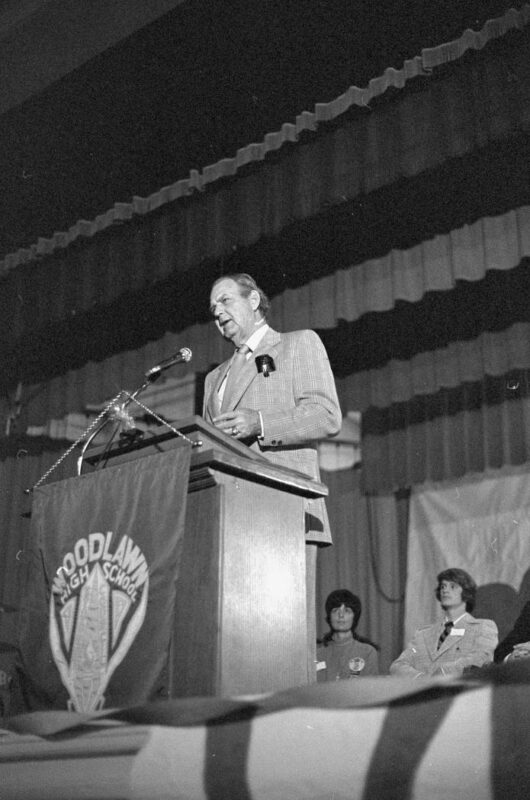

Civic institutions grew to become major anchors of the community. Notably, Woodlawn’s library became the first branch of the Birmingham Public Library after annexation. In 1922, Woodlawn High School was built on the Wood Family Springs site, and the Gibson School saw a new facility in 1925. In 1926, the City of Birmingham acquired the Edmund Wood Home, known as Willow Wood, transforming it into Willow Wood Park and Community House, a public park and center. These all contributed to a strong sense of place and identity for Woodlawn.

The 1930s brought air transportation, initially benefiting the city but adversely impacting Woodlawn. This led to a significant rise in car traffic, severe noise pollution, and encroachment on undeveloped and residential areas. By 1929, the city’s first air service launched at Roberts Field in West Birmingham. In 1931, the Birmingham Municipal Airport was established at its current location, financed by a $1 million bond and backed by the Birmingham City Commission, Chamber of Commerce, and residents.

After World War II, the exodus of white families from older neighborhoods such as Woodlawn was driven by several factors including opportunities for new housing after years of Great Depression austerity, the ability to live further away from polluting industry thanks to automobile ownership, and concerns that black families would move into the neighborhood and integrate the community. This depleted the middle-class population of Woodlawn. The trend intensified with the court-ordered desegregation of Birmingham City Schools in September 1963, sparking student protests. In 1964, some white high school students staged walkouts, but Woodlawn’s football coach, John Howell, prevented such actions. Until 1970, parents could choose to send their children to formerly all-white schools, but after that year, black students were assigned by district, leading to the closure of many all-black high schools.

Woodlawn developed a business core in a classic small-town “main street” style centered along 1st Avenue North. A mix of retail shops, restaurants, local doctors, lawyers, and insurance served the community. Over the years these businesses would rise and fall with the fortunes of the community. However, they also contributed to the sense of independent identity that Woodlawn and its people built over time.

In 1960, Woodlawn had a population of 6,372, which increased to 6,964 by 1970 but then dropped significantly to 5,527 in 1977. Racial demographics shifted during the decade, with approximately 20% being Black and 80% white in 1970, compared to 38% Black and 62% white in 1977. The rise of the automobile in the mid-20th century brought challenges such as a more transient population, increased traffic, and competition from distant shopping centers. These changes led to demographic shifts, with lower median income, higher population density, and lower rates of homeownership.

In response, the City of Birmingham initiated revitalization efforts, supported by both local funding and expertise, along with participation from the residential and business sectors. Commercial Revitalization Districts were created across the city from downtown to the neighborhood’s main streets. Such a district was created in Woodlawn. Along with this planning designation came public improvements in sidewalks, lighting, and parking areas. Design Review for commercial district signage and renovations was established along with façade rebate encouraging business owners to make improvements that aligned with the standards. Successful initiatives like the Citizen Participation program, the Woodlawn Business Association, and Stride Forward Woodlawn positioned the community for a potential renaissance, leveraging established local infrastructure in alignment with city planning goals.

By the 2000s, many nonprofit organizations were concentrating on Woodlawn with their services. These included Cornerstone School and the YWCA. In 2004, a new city-supported nonprofit organization called Main Street Birmingham (now called REV Birmingham) was created to bring a fresh focus to neighborhood commercial districts. The program chose Woodlawn to be its home office and began working to fill vacant storefronts and attract businesses. Not long after this, the Woodlawn United effort, funded by private philanthropy, focused on Woodlawn to weave together all of the efforts into a holistic effort for community revitalization.

Over the centuries after the arrival of the Wood family from South Carolina, the community has traversed an incredible journey and is currently thriving with a surge of new businesses, a significant portion of which are Black-owned. The monumental contributions of the Wood family, Hood family, and the countless untold stories of residents, shop owners, former enslaved individuals and their descendants, and many more have collectively shaped Woodlawn. Today, the spirit of progress and unity continues as the community actively engages in neighborhood-strengthening work. This coordinated effort involves organizations such as the Woodlawn Business Association (WBA), neighborhood associations, Woodlawn United, and REV Birmingham. Today’s achievements stand as a testament to their legacies, underscoring that without their enduring efforts, the trajectory of Downtown Birmingham, Woodlawn, and even Alabama as a whole would be vastly different.

To stay informed about the ongoing revitalization and community-building efforts in Woodlawn, follow @woodlawnbhm on social media and sign up for the WBA monthly newsletter. By staying connected and actively participating in these initiatives, we can all contribute to the continued growth and prosperity of this historic and vibrant neighborhood.

Related News

-

Why we say yay to two-way streets

Filed Under: Developer, Downtown Birmingham, Filling Vacant Spaces, Front Page, Transportation, Yaysayers

REV Birmingham is a long-time advocate for making the switch to two-way streets downtown, and this is something recommended by planners studying our downtown for years. In fact, the team that developed the 2004 City Center Master Plan recommended many street changes but noted 4th Avenue North conversion should take place “immediately.” We believe this project is a catalytic moment for Birmingham – but you may find yourself wondering why that is.

-

The Key Tool for Urban Revitalization: Downtown BHM's Business Improvement District

Filed Under: Business-Proving, Developer, Downtown Birmingham, Front Page, Get Involved, Potential-Proving, Why BHM

By the time REV took on BID management in 2018, downtown had a new set of needs from its BID. Downtown Birmingham in the ‘90s had a population mainly of 9 to 5 employees. But the downtown of 2018 had a whole new population of residents and visitors throughout the day and night. We had new opportunities to create positive experiences, inviting them into more downtown businesses and public spaces, and to keep them coming back for more.

-

Introducing the six businesses that call Nextec home

Filed Under: Business-Proving, Developer, Downtown Birmingham, Filling Vacant Spaces, Front Page, Historic Preservation, Potential-Proving, Why BHM

On the corner of 3rd Avenue and 16th Street North, you’ll find Nextec, a redevelopment of the 90-year-old, 65,000-square-foot Edwards Motor Company building (also formerly known as the Sticks ‘N’ Stuff building). With experience in historic renovation, developer Michael Mouron, chairman of Capstone Real Estate Investments, began this civic project in 2021 as a space for business startups to continue their work in the Magic City – a function encouraged by REV Birmingham.