By David Fleming

REV Birmingham President & CEO

As we close out Historic Preservation Month, I want to share who advocated for the conservation of historic neighborhoods and how fundamental it is for the future of Birmingham.

New Orleans

Most of us could not imagine New Orleans, especially the French Quarter, without its historic character. It may shock you to know how close the Crescent City came to destroying itself.

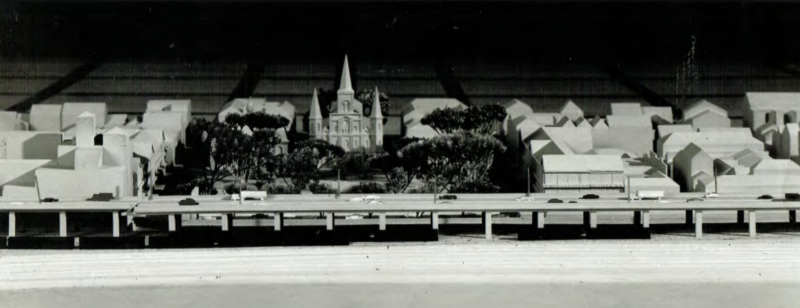

In 1946, New Orleans and the Louisiana Department of Transportation sought to modernize New Orleans’ transportation grid. The blueprint for this modernization included the construction of the Riverfront Expressway — an elevated six-lane expressway, 40-feet high and 108-feet wide — separating the French Quarter from its frontage on the Mississippi River.

Imagine sitting at Café Du Monde enjoying beignets and chicory coffee to the sound of a six-lane freeway next to your table. Or walking through Jackson Square, unable to cross the street to see the Mississippi River because an elevated freeway is blocking your path. Sadly, this idea had the full support of the city and state governments and the powerful elites in the business community. While their intentions to relieve the central business district’s perceived congestion were noble, this medicine would have killed the patient.

You might say that a second “Battle of New Orleans” ensued as local preservationists and civic activists mounted resistance to this plan by the powerful. As we can see today, historic preservation won the fight, and no Riverfront Expressway was built. We are able to enjoy beignets to the sounds of street artists and passing horse-drawn carriages instead of the roar of cars. But it took years of intentional effort to stop it and preserve the character of New Orleans.

(Images are from the June issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine)

Birmingham

In Birmingham, we treasure our historic character and neighborhoods. One such beautiful urban neighborhood is Forest Park, with its mix of stately homes and 1950s ranch-style houses close to downtown. Today we assume it always was how it is. But it, too, faced a threat.

In the 1970s, Forest Park and most of the City of Birmingham’s neighborhoods were considered to be in decline. The state of the situation cannot be better described than by Catherine Greene Browne in her book “The History of Forest Park”:

“As the 1970s dawned, Forest Park was a community of lovely older homes and picturesque, tree-lined winding roads, and it was facing a crisis that threatened to destroy the very essence of the neighborhood. Many of the older homes around the perimeter of the community had been sold to developers who leveled them and built multi-story apartments on the sites.

“Also believing the area to be a “blighted and dying neighborhood,” the City of Birmingham had plans to build a freeway through Forest Park, resulting in the destruction of many of the residences, thus, changing the very façade of the entire area.

“A group of Forest Park residents who had lived there for many years as well as more recent home buyers, met and organized the Forest Park Community Association (FPCA). Their first priority was to convince City officials that Forest Park was not a “dying” area, but rather a thriving community desiring nothing less than to be allowed to continue to survive undisturbed by unwanted intrusions.”

The community leaders Browne references were people like Bill Crocker, Catherin Browne, Sam Frazier, Chervis Isom, Hank McCarl, Robert MacLeod, Ron Council, and many others. Together, they were successful in stopping the freeway that would have carved up Clairmont Avenue, Essex Road and Cliff Road. Leaders also established a National Register Historic District and Design Review to help mitigate potentially bad development decisions by the government and the private sector. The result is one of the most stable and highly valued neighborhoods in Jefferson County.

Places in peril

There are many stories like these across the country, past and present. Places are still in peril despite newer tools like the historic tax credit to help keep historic buildings in use. Recent losses like the Quinlan Castle and current threats of loss like the Powell School prove that community-led preservation leadership is still needed to convince governments, developers, and big institutions to do the right thing by our built environment. And it takes a commitment from everyone, the public sector and the private sector, to prioritize preservation even when it is not easy.

Regrettably, many leaders who pioneered preservation efforts in Birmingham are passing from the scene. So my call to action is this: It is time for new leadership to emerge from all communities. We need a new unified, and intentional effort to save our historic places.

Do you like walking past Downtown Birmingham buildings from 1880 or 1920, or 1950? Do you treasure places like the Alabama Theatre and Carver Theatre? Do you enjoy showing off Birmingham to folks from out of town who do not have high expectations before they come?

We cannot assume that the places we love will be saved. We cannot assume that the government will automatically take care of our historic buildings or that preservation is given in public policy, the economic development community, or the real estate community. What we do know is that once a place is demolished, we cannot get it back.

What to do about it

We must work hard to keep Birmingham authentic, and historic preservation is the lowest-hanging yet incredibly satisfying fruit. We need community leaders to champion preservation and hold decision-makers accountable. Specifically:

- When a planning effort is underway for your community or neighborhood, advocate for historic preservation as a core value of the plan.

- If you live in or have a business in an older area not listed on the National Register of Historic Places, mount an effort to have the area surveyed and nominated to the Register.

- Start a fund that can be used to incentivize historic preservation.

- Communicate with public officials about buildings or neighborhoods you are concerned might be lost and need a focus.

- Record and tell the stories of buildings and places so that the public learns more about the value of those places and would miss them if gone. Erect historic markers or submit articles to local publications.

If you are interested in knowing how to do any of the above, we at REV Birmingham would be happy to direct you to the resources that could help you.

Let your voice be heard on historic preservation. It is essential.

Related News

-

Why we say yay to two-way streets

Filed Under: Developer, Downtown Birmingham, Filling Vacant Spaces, Front Page, Transportation, Yaysayers

REV Birmingham is a long-time advocate for making the switch to two-way streets downtown, and this is something recommended by planners studying our downtown for years. In fact, the team that developed the 2004 City Center Master Plan recommended many street changes but noted 4th Avenue North conversion should take place “immediately.” We believe this project is a catalytic moment for Birmingham – but you may find yourself wondering why that is.

-

The Key Tool for Urban Revitalization: Downtown BHM's Business Improvement District

Filed Under: Business-Proving, Developer, Downtown Birmingham, Front Page, Get Involved, Potential-Proving, Why BHM

By the time REV took on BID management in 2018, downtown had a new set of needs from its BID. Downtown Birmingham in the ‘90s had a population mainly of 9 to 5 employees. But the downtown of 2018 had a whole new population of residents and visitors throughout the day and night. We had new opportunities to create positive experiences, inviting them into more downtown businesses and public spaces, and to keep them coming back for more.

-

Introducing the six businesses that call Nextec home

Filed Under: Business-Proving, Developer, Downtown Birmingham, Filling Vacant Spaces, Front Page, Historic Preservation, Potential-Proving, Why BHM

On the corner of 3rd Avenue and 16th Street North, you’ll find Nextec, a redevelopment of the 90-year-old, 65,000-square-foot Edwards Motor Company building (also formerly known as the Sticks ‘N’ Stuff building). With experience in historic renovation, developer Michael Mouron, chairman of Capstone Real Estate Investments, began this civic project in 2021 as a space for business startups to continue their work in the Magic City – a function encouraged by REV Birmingham.